If I Forget Thee, Jerusalem

Fighting for the faithful city, restoring its Jewish essence

My parents got married on February 8, 1948, during a war of survival.

The bride, Leah (Mady) Catz, was the daughter of Efraim and Sabina Catz. In their forties, they immigrated to Palestine from Bucharest, Romania, and in 1924, established the first-ever farm in the dunes and marshes of Haifa Bay, demonstrating the feasibility of the Zionist dream of making the Jewish ancestral land bloom again. The groom, Jerusalem-born Aharon Press, was a physician and the director of the Haifa hospital serving the employees of the British-chartered Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC). His great-grandfather, fleeing Russian persecution, arrived in Jerusalem in 1850. His grandfather, Haim Press, participated in the revival of the Hebrew language as both a scholar and the editor of Shaarei Zion (1876-1885), one of the first Hebrew-language newspapers published in Jerusalem.

Israel’s War of Independence was the culmination of a long struggle to restore Jewish sovereignty over the Jewish homeland, which had been occupied in the 7th century by newly-Islamized Arabs, in the 16th century by the Turkish Empire, and in 1917 by the British Empire. It was a war for liberation, fought against soldiers from seven well-equipped Arab armies and Arab and Muslim volunteers, all bent on the ethnic cleansing of 628,000 democracy-practicing Jews; and against the hostility of world powers, bent on supporting and appeasing 100 million subjects of oil-rich Arab tyrannies.

The war lasted from November 29, 1947, when the UN passed a resolution calling for the establishment of a Jewish state and an Arab state in Palestine, until July 1949, when the last armistice agreement was signed between Israel and Syria, following similar agreements with Egypt, Lebanon, and Jordan. These cease-fire agreements did not acknowledge the existence of the Jewish state. Jordan occupied (and later annexed) Judea and Samaria (the “West Bank”) and the eastern part of Jerusalem, including the Old City and the City of David, which was established as the capital of the Jewish Kingdom around 1000 BCE.

My grandfather, Yeshayahu Press, was born in Jerusalem’s Old City in 1874. He has labored diligently to reclaim Jerusalem's Jewish character, reviving ancient Jewish traditions while participating in the work of new Hebrew-based research and educational institutions, as well as in the establishment of new Jerusalem neighborhoods.

Writing from besieged Jerusalem on January 4, 1948, Yeshayahu congratulated my father on his engagement. He received the exciting news “from Mrs. Satner,” who was probably the owner of the only telephone in his neighborhood, but she could not provide him with any further details about his future daughter-in-law. My father’s letter announcing his engagement, reaching Jerusalem from Haifa a few days later, still left him ignorant regarding the betrothed’s name, stock, and potential dowry, complained Yeshayahu, reporting that an Arab sniper’s bullet went through the window on the second floor of his house and lodged in a bookcase, for the second time in three months.

On January 13, Yeshayahu, now apprised of the name and lineage of my mother (but still not sure what was Sabinya (the model farm her father established in Haifa Bay and, in 1948, part of Kiryat Bialik, a Haifa suburb), responded to his son's request for advice regarding where to have the wedding ceremony: “In normal times, we would come to Haifa, or you would celebrate your wedding together with our Gold Anniversary in Jerusalem. But in these times of emergency, one must give up worldly pleasures. Last night was a night of horrors in Jerusalem. You probably learned from the papers about the two-hour battle that took place after midnight. Only people with strong nerves will get through these difficult times.”

Strong nerves were very much required for what came next: “A series of explosions which literally rocked the city and which were clearly designed to shock the Jewish population and break its morale,” wrote Dov Joseph in his memoir The Faithful City: The Siege of Jerusalem, 1948. [1]

The first of these, on February 1, completely wrecked the building of the Palestine Post, an English-language newspaper established in 1932 by Jewish journalists. The surrounding buildings caught fire, and a sea of broken glass lay scattered across the streets. A truck filled with dynamite had been parked next to the building, driven there by British policemen whose original target was a nearby movie house, but the audience had already left when they got there. On February 13, a squad of British soldiers arrested four young Haganah (Jewish defense organization) men and, instead of taking them to a nearby police station, released them, unarmed, in the middle of a mob of rioting Arabs outside the Damascus Gate of the Old City. They were lynched on the spot. On February 22, three British army trucks loaded with dynamite exploded in Ben-Yehuda Street in the center of Jerusalem, driven there by British soldiers, deserters. Six-story buildings crumbled, others caught fire, and it took more than 24 hours to complete the rescue work. Fifty-two dead were found, and 123 were wounded.

Yeshayahu lived in the house he built in 1909 in Zichron Moshe, a new modern neighborhood he established with other scholars and professionals, about a mile from Ben-Yehuda Street. His wife, seventy-year-old Miriam, was in ill health. Living with them were forty-nine-year-old Chaya, their disabled eldest daughter, who was suffering from several illnesses (many of Yeshayahu’s letters discuss her medications and the difficulties of obtaining them); and her twenty-four-year-old son David, who spent a significant part of each week in the trenches defending Jewish Jerusalem.

On February 25, 1948, Yeshayahu wrote to my father: “From mother’s letter, you could guess our mental distress after the recent events. The destruction on Ben-Yehuda Street and the surrounding area is horrible. The streets are still full of piles of stones, roof shingles, bricks, and glass shards. Our windows were shattered, and the front door was damaged. We cannot leave the house after 6pm when the shootings start, and people are killed and wounded. Yesterday, bullets flew over our house. No wonder our nerves are shattered.”

Completing his forty-year work on the Topographical-Historical Encyclopedia of the Land of Israel (Palestine) proved difficult in these conditions. “My work productivity has significantly deteriorated,” complained Yeshayahu.

The first volume of the Encyclopedia was printed in 1946, and after many delays, the galleys of the second volume were printed at the beginning of 1948. “We started preparing the illustrations and the map of Jerusalem [which was to be included in the volume, which ended with the entry on Jerusalem],” wrote Yeshayahu, but the work was halted by “the tragedy of the publisher, Rubin Mass, whose excellent son died a hero near Kfar Etzion.[2] Then there was the Palestine Post event, and then [the bombing in] Ben-Yehuda Street where the printer is located. Yesterday I visited the printer and found that the galleys and the printing paper were miraculously preserved. Still, the strong blast wreaked havoc there, and the workers were busy fixing and rearranging everything.” And he added: “When we hear about those killed and wounded in Haifa, our anxiety increases; the same for Haim in Tel Aviv. Please don’t go out at night.”

Tel Aviv-based Haim Press, Yeshayahu’s other son, was also born in Jerusalem and, in 1948, served as the director of the agriculture department of the Association of Farmers in the Land of Israel (later known as the Farmers’ Federation of Israel). At the same time, he was also active in the Haganah, which he joined in the early 1940s. Writing to Aharon on March 4, Haim apologized for not answering the latter’s letters, explaining that he “stayed for a while in the extreme South, busy with current matters.” These were code words for the benefit of British Intelligence, as Jewish volunteers defending Jewish settlements from Arab attacks were doing so illegally, as far as the British were concerned.

Responding to Aharon’s question about increasing their financial assistance to their parents, given the rapid price inflation, Haim wrote: “I can’t tell you how much more they spend now… In fact, the situation in Jerusalem is such that there is nothing to spend money on. There is nothing to buy.” The rest of the letter is devoted to what became the main topic of conversation in the letters exchanged between the brothers and in their father’s correspondence with them—food. Haim sent their parents a package with agricultural products and asked Aharon to send sugar and rice if he could find them. There was no cooking oil in Jerusalem, and he could not find any in Tel Aviv.

The Arab residents of the villages around the only road connecting Tel Aviv to Jerusalem set up roadblocks and fired at Jewish vehicles and convoys, with no interference by the British army and police forces. Dov Joseph: “By the third week of March, a food convoy had failed completely, for the first time, to get through to the city. Jerusalem was now truly besieged. By the end of the month, it was fair to say that only two weeks’ supply of emergency foodstuffs stood between Jerusalem and starvation.”

Starvation or annihilation by superior forces, armed by superior weapons and animated by Jew-hatred. Zipporah Borowsky, a young American who came to Jerusalem for a year of study at the Hebrew University, wrote about living in Jerusalem in 1948: “There was hardly a single day or night, barely a single hour without an ever-present barrage of shootings, incessant explosions, merciless shelling, shrieking cries for help, without somebody being killed or wounded. Never a letup from constant fear and terror.” [3]

On March 14, Miriam Press wrote to Aharon that the stress affects her eyesight, but she wouldn’t go to an eye doctor because she might get shot—"I want to live and see you.” And she added: “Don’t worry, what will come will come.”

What arrived only four days later was foreign news perceived as terribly shocking by Aharon and many other Palestinian Jews. Warren Austin, the U.S. ambassador to the UN, announced that the U.S. now supported a UN “trusteeship” for all of Palestine rather than the Partition Resolution, which it had voted for in November 1947. In addition, says Jeffrey Herf, “in Spring 1948, the State Department used the machinery of UN Security Council truce resolutions to prevent further Jewish immigration, especially of military-age Jewish men, and to block delivery of any military equipment to the Jewish Agency.”

On March 21, Aharon wrote to Haim: “Low spirits today following the American announcement. Who knows what will happen? The disappointment is akin to that of a hungry person who is served a tasty dish, only to have it taken away from him all of a sudden. I would comfort myself with à quelque chose malheur est bon [every cloud has a silver lining]. Perhaps because of the new arrangement, we will eventually have the entire country!” My mother added in her neat hand that they couldn’t get fish and meat for a week, so the eggs Haim sent “helped a lot.”

Dov Joseph called the American announcement a “bombshell” that was “regarded by the Jews [in Palestine] as a direct betrayal… In Jerusalem… people seemed to recognize that the new development only confirmed the inevitability of a bigger and more bitter military struggle. … The American plan was [eventually] whittled down… but it encouraged the Arabs to continue their refusal to agree to a truce or to accept a partition, and it gave support to the British elements still determined to nullify the UN decision.”

Another young American, Mordecai Chertoff, who, like Zipporah Borowsky, came to Palestine on a student visa but, in his case, ended up as a Palestine Post reporter and editor, wrote to his parents on March 21: “Excuse the bitterness…What a bunch of no-good, filthy, scurvy, stinking, bastardly double-crossers!... [The Chairman of the Jewish National Council, David] Remez answered nicely, last night: ‘As long as there’s a Jew left alive in Palestine, he’ll be a free man.’ … We’ve been betrayed and we stand alone… When we find potatoes, we’re going to roast them over a fire of [our] American passports.” His sister Naomi, back in the U.S., wrote to him: “They betrayed us first in Europe and now in Palestine.”

The British sustained this betrayal with their anti-Jewish actions. Dov Joseph: “The uncertainty of the British policy was its most baffling, and to us, one of its most costly aspects. We could be certain only of what they did not want, and this was chiefly three things: no Jewish immigration in excess of 1,500 permitted every month [and the hunting down of immigrants who managed to slip through the British blockade]; no constructive help by anyone else, including the UN, toward implementing partition; and no creation of even a shadow Jewish state, at least while they remained in the country.”

These policies were translated into murderous actions by British policemen and soldiers. On April 13, a convoy to Hadassah Hospital on Mount Scopus, Jerusalem (where the Hebrew University was established in 1925), was ambushed by Arabs from the Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah. Seventy-eight Jewish doctors, nurses, students, patients, faculty members, drivers, and Haganah fighters guarding the convoy were killed. Many of the bodies were burned beyond recognition. The British Colonial Secretary and the British High Commissioner for Palestine had given assurances that medical and civilian convoys would be given British protection. For seven hours, however, the British refused to intervene—a British position was 200 yards from the attack—and stopped a rescue attempt by the Haganah. British army convoys and ambulances passed the crippled Hadassah vehicles but ignored the attack and cries for help. The Arab Higher Committee, established by the members of the Arab League (Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen) as the supreme executive body of Palestinian Arabs, praised the attack and stated that “Had it not been for [British] Army interference, no Jewish passenger would have remained alive.”

Dov Joseph: “Great Britain, the mandatory power, was closing out its thirty-year trusteeship of the Holy Land in a mood compounded of bitterness, defeatism, and die-hard vengefulness…. Our tragedy was that our final fight for freedom, after two thousand years of exile, came at a moment when a war-weary nation, unwilling to go on paying the price of empire and unwilling to give it up, was capable only of massive, wavering indecision…”

That was true of the British throughout the time they administered the Palestine Mandate, which was accorded to them by the League of Nations in 1920, to establish there a “national home” for the Jews. Preserving its empire and sphere of influence, the British (led by the Colonial Secretary, Winston Churchill, and the Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon), created “Transjordan,” giving most of the mandate’s territory to Abdullah, the son of Hussein, the Emir of Mecca.

As Orde Wingate explained in 1937: “The administration of Palestine and Transjordan is, to a man, anti-Jew and pro-Arab. This is largely due to the fact that we seem to send only the worst type of British official to Palestine. They hate the Jew and like the Arab who, although he shoots at them, toadies to them and takes care to flatter their sense of importance.”[4]

In 1938, the Palestine Partition Commission (the Woodhead Commission) was established to propose a detailed partition scheme for Mandatory Palestine, following the two-state solution recommended by the Peel Commission (accepted by the Zionists, rejected by the Arabs). In response to the Peel Commission’s proposal to include Jerusalem in a “mixed Corridor State” (i.e., not in the proposed Jewish or Arab states), Yeshayahu wrote a long memorandum, “The Historical Connection of the Jewish People with Jerusalem,” which was submitted to the Woodhead Commission by the Jewish Agency.

It opened with “Every scheme for a Jewish political restoration in Palestine, from the proclamation of King Cyrus in the third century BCE to that of Napoleon at the threshold of the nineteenth century, was expressed in terms of the rebuilding of Jerusalem.” The key theme of this memorandum was “the two-fold significance, spiritual and secular, of ancient Jerusalem to the Jewish people,” which is “being realized afresh in the New Jerusalem of our day.”

In subsequent years, Yeshayahu published many articles urging the restoration of this spiritual and secular significance, in response to British attempts to de-Judaize Jerusalem and to what he perceived as increasing neglect by his fellow Jews. With the Hebrew Association for Jerusalem, he established additional channels for promoting and sharing his vision for Jerusalem, both old and new.

The Association was founded in late 1942, with Yeshayahu as its chairman and Yitzhak Ben-Tzvi (President of the Jewish National Council) and Rabbi Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel (Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Palestine) as co-presidents. Its first public appeal was published in local newspapers in April 1943: “If I forget thee Jerusalem, may my right hand forget its cunning! In this perilous hour for our people, let’s bring the remembrance of Jerusalem to the top of our considerations. Every step in our city of birth reminds us of its glorious past, but the numerous remnants of this past are neglected and are not preserved.”

Yoram Elmakias writes that the association’s founders “worried about what they perceived as a deliberate policy by the British authorities to minimize the city’s Jewish past and to emphasize its universality as the city of three religions.” They were also concerned about the neglected ancient Jewish sites. For example, the tombs in the Kidron Valley were constantly damaged by the Arabs of Silwan, and the Tombs of the Kings were in French hands. The archaeological excavations at the city of David were used as a garbage dump, and stones were taken from the ancient walls to be used in construction.

Yeshayahu later wrote about the synagogues of the Old City: ”Since the Arab riots [in the mid-1930s] intensified and drove most Jews out of the Old City where they had lived for generations, I have been communing, once a month or every two months, with the place where my cradle stood and my mother sang me lullabies… Walking alone in the streets of the Old City… my heart sank seeing the courtyards the Jewish homemakers cleaned and beautified for Shabbat every Friday evening, now drowning in the muck and filth of the Arabs who occupied the former homes of Jewish residents…”

With its meager funds from membership fees and donations, the Association attempted to revive the Jewish presence in the Old City, including finding and redeeming Jewish property, encouraging Jews to return to live there, and supporting the Old City's industry and artisans. Already in the 1930s, Yeshayahu compiled a list of abandoned Jewish properties in the Old City. In 1949, the Association (with the Rabbi Kook Foundation) published the second volume of Yerushalayim (Jerusalem), its research annual.

In his article for this volume, titled “If I Forget Thee, Jerusalem,” Yeshayahu provided an updated list of Jewish properties in the Old City, writing that “at this time, we can’t assess the extent of the destruction in the Old City in general and the Jewish Quarter in particular, and the political status of the holy city is still unclear. But one thing must be clear to us: we shall never give up our share of the sacred city. We must rebuild the ruins and reconstitute the Jewish Quarter in utmost splendor and magnificence.”

To disseminate knowledge about and foster appreciation for Jewish Jerusalem, the Association organized study tours in both Old and New Jerusalem, as well as other educational activities. “We wanted to renew in our generation the longing for the holy city, which moved our ancestors in previous generations over deserts, steppes, rivers, and seas to reach our rock of the ages,” Yeshayahu wrote about the Association. “Among other activities, we hoped to achieve this goal by renewing the pilgrimage to Jerusalem.”

Following the Hebrew bible, which instructs all able Israelite males to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem three times a year, the Association developed a detailed pilgrimage plan, starting with school-age youth, continuing with all of the country’s Jewish residents, and then expanding it to Jews in the diaspora.

In the summer of 1945, the Association organized the first tour of the Old City for the new graduates of Jerusalem’s elementary schools (aged 13 and 14). It continued doing so for another two years. “In mid-June 1947,” recalled Yeshayahu in his memoirs, “all the new graduates met at the courtyard of the Lemel school, marched to the Old City, and visited the great synagogues where they heard from their teachers about their history.”

Next, the children arrived at the Western Wall. More or less spontaneously, they started singing Hatikvah (The Hope, the Zionist anthem). The British policemen stationed nearby burst into the crowd of children, pushing and shoving, but the children continued to sing Hatikvah to the end. “When the policemen asked who was responsible for this criminal act,” wrote Yeshayahu, “I surrendered to them.”

This was the second time Yeshayahu was arrested. The first time, “also in the context of educating the children of Israel,” by the Turkish police. In 1905, the third annual meeting of the Teachers’ Association, which Yeshayahu co-founded and helped manage in its early years, took place at the Lemel School in Jerusalem. When the first day’s meeting adjourned late at night, the Turkish police, which avoided entering the school (funded by Ha’Ezra—a philanthropic association of German Jews—it was considered the property of a foreign power), arrested the three Ottoman citizens at the meeting: Yeshayahu, David Yelin, and Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (the other attendees maintained their foreign citizenship when they immigrated to Palestine and were under the protection of their respective foreign consuls).

When the head of Ha’Ezra in Palestine and the German and Austrian consuls pleaded for the prisoners with the Ottoman governor of Jerusalem, he said he had already sent a report to Constantinople about the unlawful meeting of the prohibited “Zionist association.” Eventually, convinced that the only goal of the Teachers’ Association was to improve the teaching in Jewish schools, he released the prisoners.

Forty-three years later, the British were quicker to relent. Yeshayahu: “I was released from police custody due to the testimony of two Jews who happened to come by, who supported my claim that Hatikvah is a prayer and, as a prayer, cannot be forbidden at the Western Wall.”

As it turned out, this was the last—until the establishment of the State of Israel—school-organized tour of Jerusalem and pilgrimage to the city. “The events (המאורעות) that followed later that year prevented us from continuing this activity,” wrote Yeshayahu.

“The events” has been the euphemism used by Hebrew-speaking Jews to designate Arab pogroms in Palestine, and just like pogroms in the diaspora, they have been identified by the year the “event” happened. For example, מאורעות תרס"ח designate the 1908 attacks on Jews by Arabs in Jaffa during the Jewish holiday of Purim. In English, this “event” is usually called “the 1908 Jaffa Riots,” using an English-language euphemism, typically applied to all Arab-led pogroms in Palestine, which intensified in scale and scope after the British conquest in 1917.

“The events” or “riots” of late 1947 were sparked by the United Nations. On November 29, 1947, the UN adopted Resolution 181, which recommended the creation of independent Arab and Jewish states in what had been the British Mandate of Palestine (or what remained of it after the creation of Transjordan) and an extraterritorial "Special International Regime" for the city of Jerusalem and its surroundings. The Jews—in Palestine and elsewhere—celebrated the international community's recognition of their right of self-determination.

After a night of celebration (and putting together a new issue of the Palestine Post with the headline “UN Votes for Jewish State”), Mordechai Chertoff wrote the next day: “We heard a tremendous roar from Ben-Yehuda Street, ‘David Melech Yisrasel Chai Chai Vekayam’ [David, King of Israel, lives eternally], and the roar is repeated again and again from the throats of the youth of Jerusalem banding together in a huge ‘hora’ around an armored police car. … And another ‘hora’ in the [Jewish Agency] building courtyard, men and women in pajamas, half-dressed but completely awake…. And suddenly the blue and white appeared on a balcony, and a jubilant and fresh ‘Hatikvah’ which we had never dared to hope for and never anticipated, erupted from five thousand mouths. … The People of Israel dwell on its land once more—and we are the last generation of slavery and first generation of redemption.”

Also witnessing the jubilation in Jerusalem was Zipporah Borowsky, who wrote to her family at 11 am on November 30: “In the center of town, crowds of happy people, hugging each other, dancing horas and jigs, headed spontaneously, as we were headed—drawn by some magnetic force—to the courtyard of the fortress-like Jewish Agency building. Out came a flag, and onto the balcony came Golda Meyerson [Meir]. There were no words to suit the moment. Choked with emotion, she managed to say ‘Mazal Tov,’ and down came tears, oceans of unrestrained, happy tears.”

Borowsky described how David Ben-Gurion, arriving later from Tel Aviv, stood on the same balcony and told the crowd, “Ashreynu shezachinu layom hazeh (blessed are we who have been privileged to witness this day),” followed by “Techi Hamedinah Ha’ivrit (long live the Jewish state).” After the crowd sang Hatikvah, “Ben-Gurion tossed his head back proudly, tenderly touched the flag that hung from the railing and charged the air with electricity when he shouted defiantly: ‘WE ARE A FREE PEOPLE.’”

Free and democratic people. The Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine elected the Assembly of Representatives to serve as its provisional parliamentary assembly. It was established on April 19, 1920, and functioned until February 13, 1949, the day before the first Knesset (Israel’s parliament) was sworn in. The Assembly met once a year to elect the executive body, the Jewish National Council, which was responsible for education, local government, welfare, security, and defense. The assembly, recognized by the British authorities in 1928, was elected periodically through secret and direct voting by all 20-plus Jewish men and women residing in Palestine.

In contrast, the Arabs in Palestine continued to be ruled, as they had been for centuries, by the local nobility. Neither the Palestine Arab Congress in the 1920s and early 1930s, nor the Arab Higher Committee of the 1930s, was an elected body. They represented the major, often warring, families of Arab notables and were controlled mainly by the Husayni clan. In November 1945, the Arab League reconstituted the Arab Higher Committee as the supreme executive body of Palestinian Arabs (the British outlawed it during the bloody revolt of the Arabs in Palestine in the mid-1930s). The committee was (again) dominated by the Husayni family and was recognized by the British two months after its establishment.

The November 29, 1947, UN resolution 181, the partition resolution, read, in part: “The Provisional Council of Government of each State shall, not later than two months after the withdrawal of the armed forces of the mandatory Power, hold elections to the Constituent Assembly which shall be conducted on democratic lines… Women may vote and be elected to the Constituent Assemblies.”

The same Arabs—in Palestine and elsewhere—that had refused to accept the presence of Jews in Palestine, also declined to accept these foreign notions of democracy and women’s equality. The result was attacks on Jews throughout Palestine and in Arab countries.

In Jerusalem, the first shots were fired on November 30, at an ambulance on its way to Hadassa hospital on Mount Scopus. On December 2, two crowds of several hundred Arabs, armed with sticks, stones, and some firearms, advanced from the Old City into the predominantly Jewish sections of the New City. They smashed windows, looted shops, and attacked Jews. When Jewish organized defense units went into action, they were quickly disarmed by the British police; some of the confiscated arms were later found on killed and captured Arab rioters. By December 4, the Arabs in the Old City were breaking curfew with impunity and attacking synagogues.

In other matters, the British were even more decisive and resolute. During December 1947, approximately 15,000 Jewish refugees (almost all of them Holocaust survivors) were denied entry to Palestine. This, regardless of the clear language of UN Resolution 181, which required the British to “ensure that an area situated in the territory of the Jewish State, including a seaport and hinterland adequate to provide facilities for a substantial immigration, shall be evacuated at the earliest possible date and in any event not later than 1 February 1948.” The British administration refused to comply, sticking with its monthly quota (announced in May 1939) of 1,500 immigrants.

Regarding Jerusalem, the British had also been consistent. In March 1945, the British High Commissioner put forward a proposal to solve the “deadlock in the affairs of the Jerusalem municipality by a scheme of annual rotation of the office of mayor between the Moslems, Christians and Jews and by the addition of two British councillors,” reported a year later the British administration. It continued: “The adverse reaction of the Arab press and public was immediate, and a protest strike was observed in Jerusalem, Haifa, and the main Arab towns on 24th March. The Arab councillors refused acceptance of a Jewish mayor in any circumstances.” [5]

The British High Commissioner then asked Sir William Fitzgerald, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in Palestine, to investigate the situation and make recommendations regarding the administration of Jerusalem. Fitzgerald wrote that “the foundation upon which English municipal government rests is recognition of the fundamental principle of democracy that the opinion of the majority shall prevail.” But as Jews constituted 61% of the population of Jerusalem at the time, “the Arabs are unable to concede the application of that principle to the city of Jerusalem... In the light of history, I am constrained to admit that this point of view, although not to the extent to which it has been pressed by the Arabs, is not without substance.”

So what’s to be done “in the light of history”? Change the facts of the present to accommodate Arab hostility to democracy and the Jews. In this case, redefine “Jerusalem.”

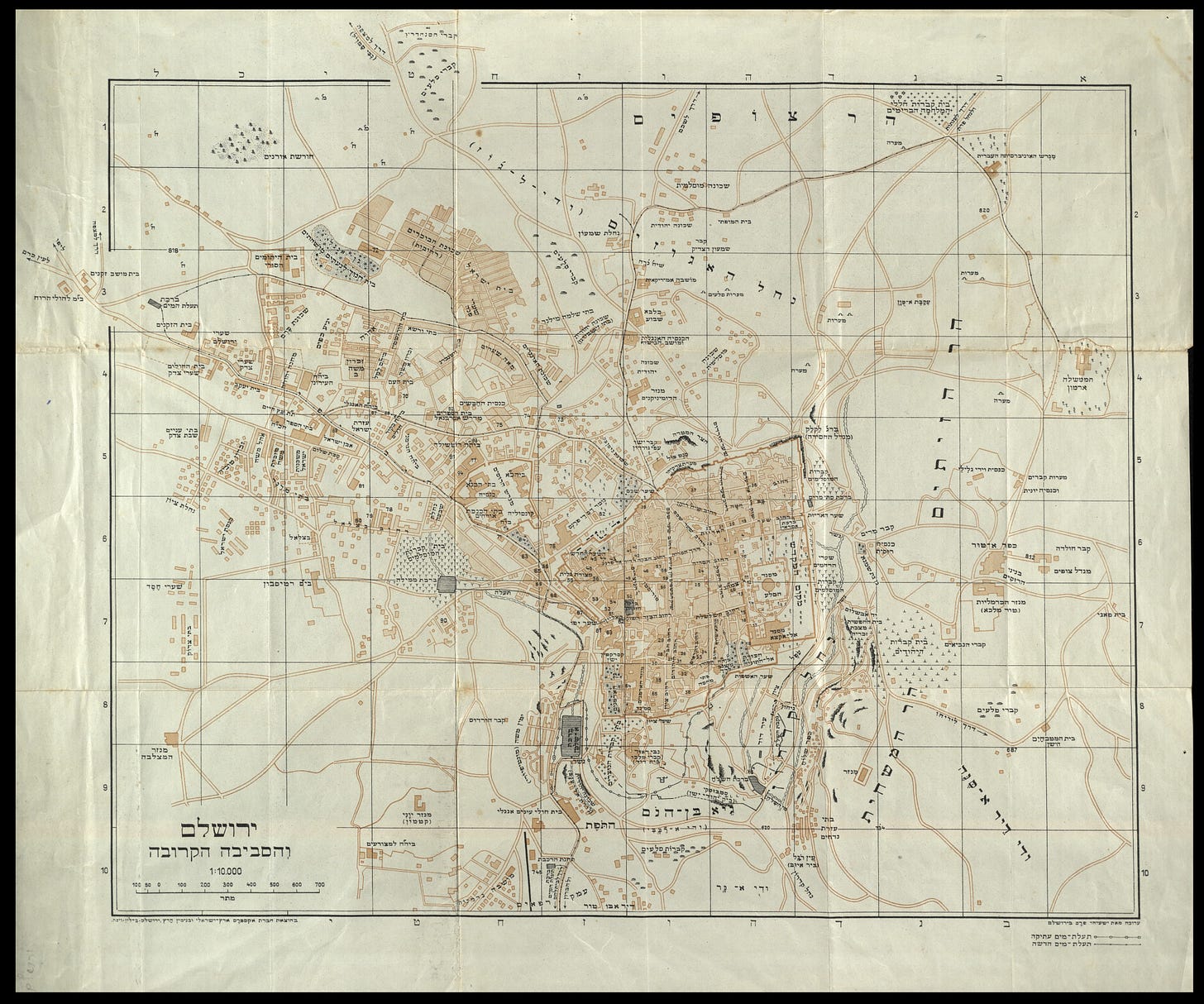

Fitzgerald proposed the partition of the Jerusalem municipality into three separate municipalities: A Jewish city and an Arab city, both run by a council, the members of which would be elected (!) by the residents of their respective areas; and an administrative municipality comprising the Old City and the area to its east, including Mount Scopus (seat of the Hebrew University) and the Mount of Olives (and its Jewish cemetery), jointly managed by the British administration and representatives of the other municipalities. Fitzgerald attached a newly drawn map of Jerusalem to his report.[6]

Reacting to this new map, which expanded the area of Jerusalem beyond the boundaries of its official plan, Yeshayahu calculated that the addition of Muslim and Christian villages meant the addition of about 38,000 Arabs, thus equaling the proportion of Arabs in the Jerusalem population to the Jewish one.

Beyond the geographical and demographic adjustments to Jerusalem, however, the new British maps also raised further concerns for Yeshayahu about the erasure of Jerusalem's Jewish character. In a February 1947 letter to Moshe Shertok (Sharet), the head of the foreign relations department of the Jewish Agency, he wrote: “The maps of Jerusalem published so far obscure to some extent the Jewish elements, both historical and of the present. We must, therefore, publish a Jewish-Hebrew map of Jerusalem, highlighting Jewish antiquities, the Jewish presence in our time, synagogues, places of learning, and public and national Jewish institutions.”

Yeshayahu continued his crusade for Jewish Jerusalem during the war for the city, writing in a February 11, 1948, letter to David Ben-Gurion: “The decision of the UN to exclude Jerusalem from the Jewish state greatly crushed the soul of the Israelite nation, and turning the holy city and its surroundings into an international [UN-administered] area, a fabrication without parallel in world history, forms the basis for our grave apprehension about the future of the eternal city… The systematic and intentional process of dispossessing us from the Old City, which began with the British conquest, should serve as a warning sign… We must restore the original splendor of Jerusalem [so it would serve] as a religious, spiritual, and cultural center for the entire world…We must increase the number of Jewish residents in the [proposed] international area of Jerusalem and fortify our position, so we will be ready at the right time to insist on our rights.”

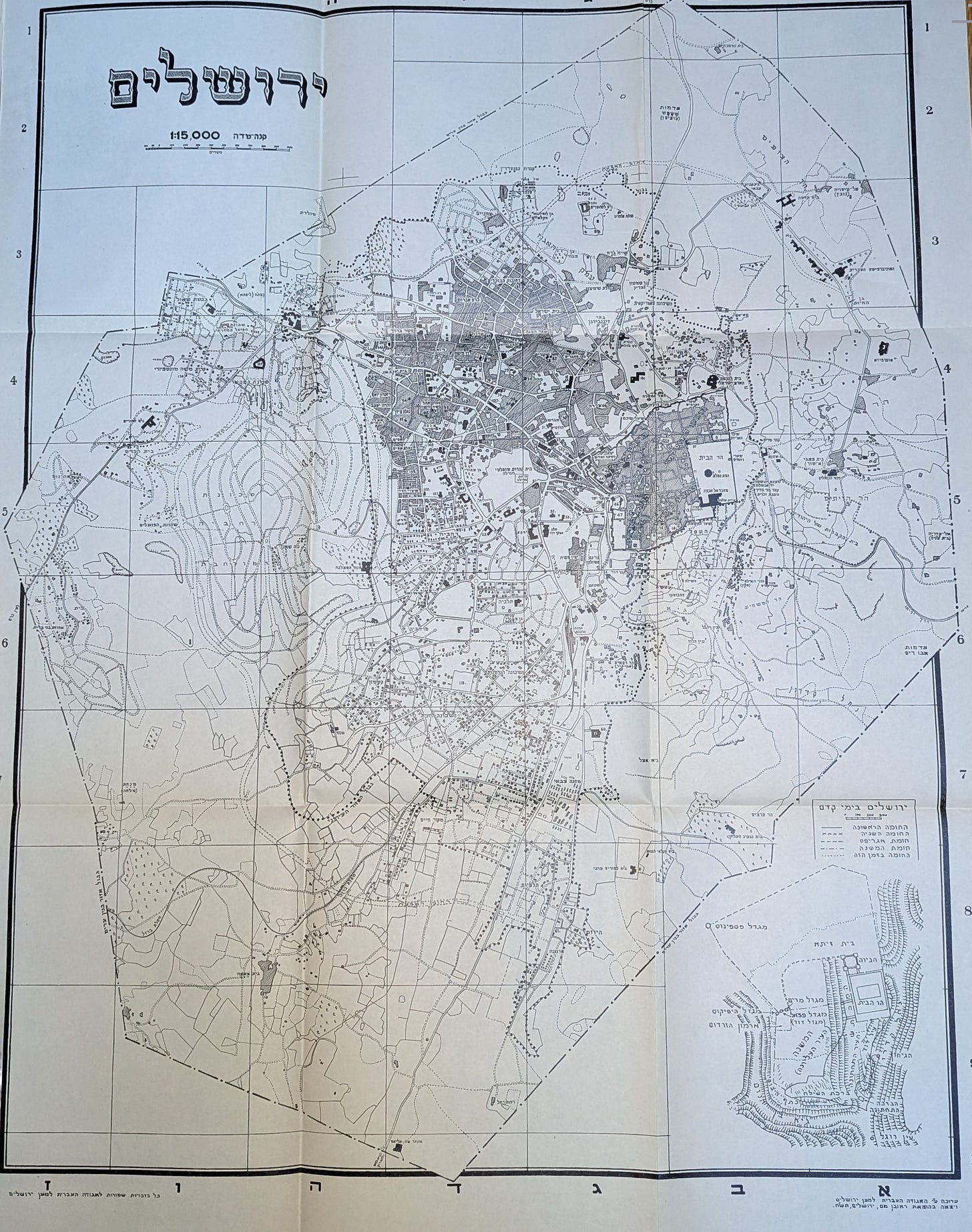

In early March 1948, bound copies of the second volume of Yeshayahu’s Encyclopedia were finally ready. Yeshayahu wrote in the Preface: “The publication of the second volume, which includes thousands of additional entries, ensures that the book's printing, which commenced six years ago in the most difficult conditions, will continue and be completed in the next few years. … a new map of Jerusalem, which reflects in particular the Jewish character of the city, is attached to this volume.”

This “unique map of Jerusalem,” as Elmakias calls it, which was also published separately by the Hebrew Association for Jerusalem, “clearly reflects the vision of the Association and its goals, by emphasizing the fact that Jerusalem is a Hebrew, national, ancient, and modern city.”

On March 18, 1948, the Association distributed a memorandum to Jewish policymakers in Palestine: “The decision by the UN not to include Jerusalem in the proposed Jewish state is a grievous affront to the soul of the nation of Israel. The systematic and intentional process of our dispossession from the Old City since the British conquest should serve as a warning that we cannot disregard this vital issue. We must restore to Jerusalem its original splendor as a religious, spiritual, and cultural center of world Jewry.”

Citing the goals of the Association—”To boost and raise the esteem of Jerusalem in our eyes and the eyes of the world and strengthen the appreciation of Jerusalem as the eternal city of the nation of Israel”—the memorandum recommended investing in developing the university, institutes of research and higher learning, Yeshivot, and teachers’ seminaries; bringing to Jerusalem all the literary and art treasures stolen from the Jews in Europe; absorbing in Jerusalem a significant part of the new immigration, especially those depended on institutional support; developing Jewish tourism to Jerusalem; and encouraging private initiative, including establishing industrial plants and at least 200 small farms.

Yeshayahu personally delivered the memorandum to David Ben-Gurion and the Jewish Agency later asked for 40 copies. “Apparently, we made an impression,” Yeshayahu noted.

Writing on April 14, the day after the Hadassah convoy massacre, Yeshayahu lamented the British refusal to intervene, the burned bodies buried in a mass grave, and the “crowded funerals” going by his house. He added, “We live here at the front, twenty-four hours a day, we hear the sounds of shooting and shelling. David [his grandson] is in the trenches three times a week, twice for 24 hours and once for 12 hours. Unfortunately, the people in the trenches get awful food.”

The shelling of the city, which started on April 10, intensified after the British left Jerusalem and was directed by British officers of the Arab Legion. Dov Joseph: “Day after day and night after night, throughout the siege, the Arabs continued indiscriminate shelling of the city almost without respite, frequently using incendiary shells which caused fires. On some occasions, the shells came with enervating regularity every two minutes, a kind of Chinese torture as one waited for the next shell to explode… to have to sit helplessly while the Arabs cannonaded the city day after day and night after night, killing and wounding hundreds of civilians, in the knowledge that we had no comparable cannon with which to hit back, caused more chagrin and did more to undermine public morale than almost any other single hardship our public were called upon to endure.”

As the British were evacuating their administrative personnel, the postal service in Jerusalem was terminated on April 25. Three branch offices were opened on May 9, and Yeshayahu sent letters to Haim and Aharon, probably using a Jewish National Fund label as a stamp (Doar Ivri—Hebrew Post—stamps were available in Jerusalem only on June 20, and the State of Israel stamps on July 4):

“Finally, we can send you news from home via the Hebrew post office, which starts operating today. We were not hurt by the shootings and shelling over the last month; the only reminder is a bullet stuck in the external door.”

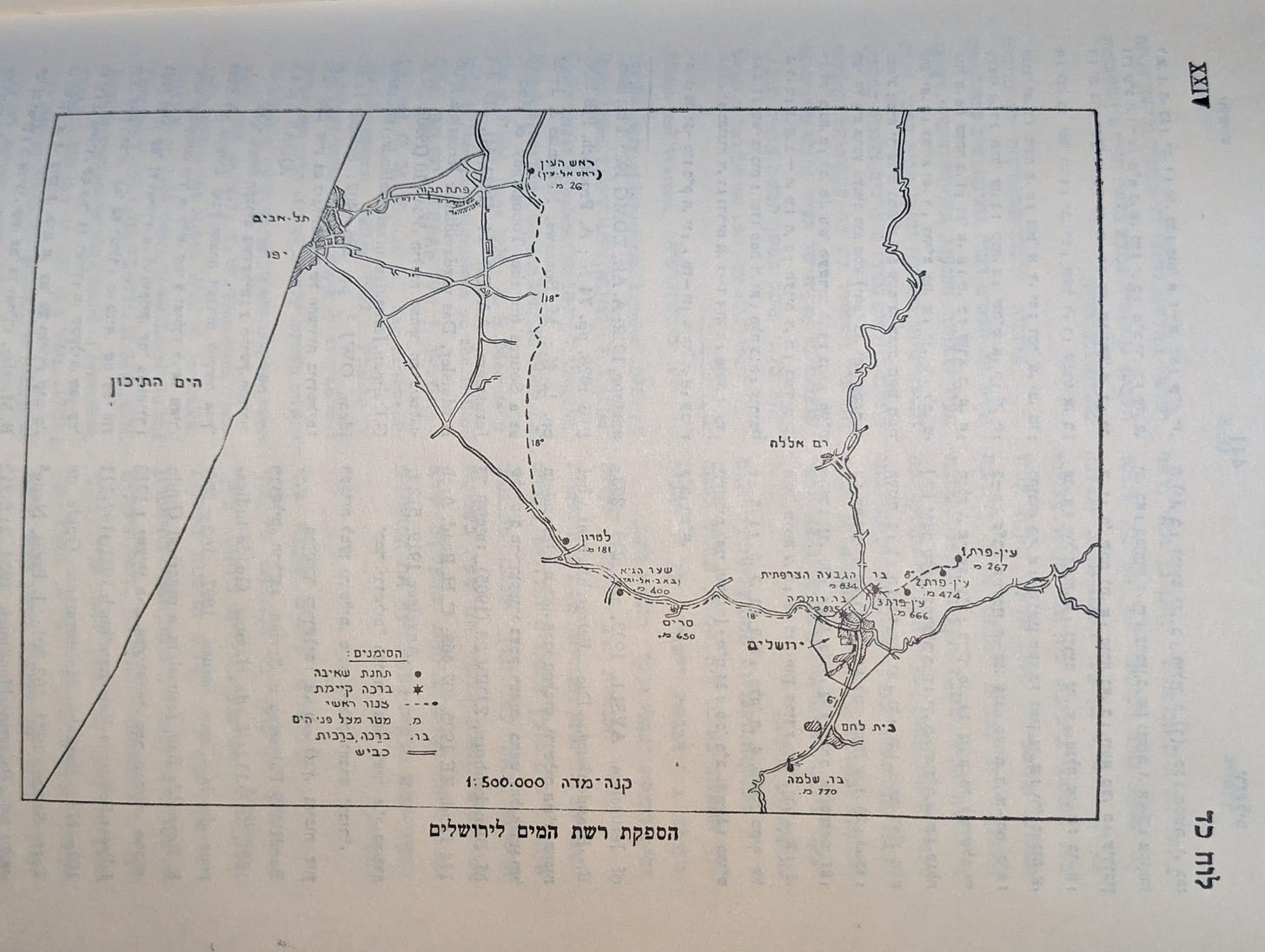

Yeshayahu reported that Jerusalem turned into a fortified city, with bomb shelters everywhere. The Civic Guard (Mishmar Ha’am) set up a public shelter in the basement of their house and erected a cement wall at its entrance and around the heating furnace. All the pieces of wood they could find were used for heating, including wood Yeshayahu chopped from a fallen tree. The cistern in their yard was covered to preserve it for public use in case the water supply to Jerusalem is shut down.

While the war intensified for Yeshayahu and other Jerusalemites, it eased somewhat for his sons. The crucial battle for Haifa took place on April 21, when the British suddenly decided to evacuate most of the city, and it was over within twenty-four hours. In Tel Aviv, Haim told Aharon on May 13, “The mood is up. Jaffa surrendered, and there is a lot of commotion in anticipation of the declaration of independence on [May 15]. I’m afraid that people are getting too complacent and tend to forget that we will face fierce battles and suffer many casualties… Be strong and take courage, hoping for better days and our decisive victory over our numerous enemies.”

On May 28, the Old City fell to the Arab Legion, which was stopped by the newly-formed Israel Defense Forces (IDF) from advancing further into Jewish Jerusalem. Dov Joseph: “The enemy outnumbered the fighting defenders [in the Old City] by a twenty-to-one ratio and was backed by a savage mob of Arab civilians who had been shouting for weeks their determination to massacre every Jew inside the Old City.” 21 of the 27 Old City synagogues were destroyed.

Lamenting the loss and destruction, Yeshayahu wrote in an article he published a few months later: “Will the fate of the city of David be similar to that of the city of the patriarchs [Hebron]? We have finally established the state of Israel, but we would not be able to enter our holy city? Has the conscience of the world’s nations, those posing as conveyors of civilization, drowned in the oil pools?”

In early June, Yeshayahu, who hadn’t heard from his sons for a month, wrote, “Our situation is dire. Day and night, shells fall all around us. Last Thursday at 4am, a shell hit the hut in the parking lot adjacent to our house. The shell shards destroyed the pine tree near the house, entered our dining room through the door and the iron shutter, and hit the wall and the ceiling. On Saturday, a phosphorus fire bomb fell near our house, which we snuffed out with dirt… We sleep on the floor separately, each one of us in a corner of the room, to better protect ourselves from shell shards, which fly upwards, as we learned from experience. The constant bombardment is very stressful.”

There was no electricity, and David, their grandson, was now fully engaged in the war. Their neighbors slept at night in their basement, which was converted to a public shelter, and during the day, people ran to it from the street for cover from the shelling. Their cistern has already been used three times for water distribution—half a can per day per person.

“In old age, I became a water-drawer and wood-chopper,” Yeshayahu wrote, ending with a quote from Deuteronomy, “The sword shall deal death without.”[7]

From June 11 to July 8, a ceasefire helped alleviate the situation in Jerusalem. On June 20, Yeshayahu informed Aharon that he had received his telegram, the first direct news from his son in more than three months. “I think you know what happened during the days of non-stop bombardment of Jerusalem from all corners of the earth. What will happen soon, only the devil (Bevin—Abdullah) knows.[8] We feel like we are sitting on a volcano, which could erupt at any moment. We especially lack heavy weaponry, which the enemy has in abundance. I would not exaggerate if I say that during the 28 days of bombardment, one hundred thousand shells and bombs were directed at our city.” Miriam added, “Not sleeping for 28 days is not easy.”

Later in June, Yeshayahu answered Haim’s and Aharon’s invitations to move to Tel Aviv or Haifa: “We are happy to have such good sons, and now a dutiful daughter, but I, born in the Old City, steps from the Temple Mount, cannot abandon the city of my birth at this difficult time. In addition, I’m in my seventies, and every hour I can free myself from the household chores, I spend on my life’s work. Even during the bombardment, I sat and worked in a more or less safe corner of the house in my room among the bookshelves. At night, there is not enough light and I can’t work. At this time, it is impossible to start printing the third volume [of the Encyclopedia] because the printing houses are closed due to a lack of workers and electricity.”

In mid-July, Yeshayahu reported that a telegram sent by Aharon from Haifa took six days to arrive. Miriam suffered from dysentery, which was widespread in Jerusalem, and he speculated it was the result of eating fresh fruits and vegetables for the first time in four months.

On July 21, Yeshayahu wrote: “Last week was a horrible week in Jerusalem, especially the last night before the [second] ceasefire, a night of terror. The bombardment started at 5pm and lasted, without interruption, for fourteen hours. The ground shook, and the sky was covered with mortars and bullets, and it felt like all were flying just above us, and that soon we would be wiped off the face of the earth. The shells hit several people in the street or when they waited in front of their houses for their share of the water distribution.” [9]

Yeshayahu added that he received a letter from Haim, written in pencil while he sheltered during the aerial bombing of Tel Aviv. From May 15 to July 17, the Egyptian air force indiscriminately bombed Tel Aviv and surrounding cities, killing 150 in Tel Aviv (almost all civilians) and injuring several hundred.

A second ceasefire, starting on July 17 in Jerusalem, was imposed by the UN Security Council on the belligerents when it became apparent that any extension of the fighting could only mean further deterioration in the Arab position, after they lost territory and 5,000 fighters in the ten days of fighting since the end of the first ceasefire. “If the inhabitants of Jerusalem hoped that the truce would bring them respite from the noise of bursting shells and gunfire and that they would at last enjoy quiet, if not peace, they were doomed to disappointment,” wrote Joseph. “For some five months, until the end of December, there were few pitched battles and there were intermittent days of complete quiet…From the very first day, we received reports of Arab violations of the truce by building fortifications, mining roads, and firing at our men… Each Arab violation of the truce was carefully reported by us [to the Truce Commission], but it did no good… rarely was an effective action taken by them, nor did they make any serious attempt to prevent their occurrence.” One of the reports, from sometime in September, was about a sudden Arab bombardment: “For over an hour, the city was rocked by the explosions and the sky streaked with tracer bullets and the flashes of the heavy guns.”

On September 20, Yeshayahu wrote to Aharon: “Yesterday I lectured to about 100 people at a B'nai Brith event about the Jerusalem problem [i.e., its proposed internationalization]. Suddenly, a heavy bombardment started, but the audience didn’t move, even though the lights were on and the windows open. The discussion continued until 9:30pm, and the audience left only when there was relative quiet. I ran all the way home with bullets flying over my head. Twice, I dodged bullets by sheltering inside house entrances. Just after I got home, the bombardment resumed and lasted until midnight.

In last Friday's bombardment, a shell entered the second-floor apartment, went through four inner walls, and lodged in a suitcase... Yesterday, a bullet entered the second-floor apartment where David Rosen, the head of the Jerusalem Civil Guard (Mishmar Ha'am), was sleeping.”

In October 1948, Yeshayahu was awarded the Ussishkin Prize for the Topographic-Historical Encyclopedia of Eretz Israel. “Owing to the war,” the Jerusalem Post reported, “the prize-giving ceremony was austere and took place in the Directors' room of the Jewish National Fund.”

In his acceptance speech, Yeshayahu ascribed the origin of the idea for his geographical lexicon to a school trip to Ein Prat (Euphrates in Jeremiah 13:4) when he was fourteen. His teachers—Efraim Cohen and David Yelin—took their students on country-wide excursions on foot to bring to life for them what they had learned in their Bible, Mishna, and Land of Israel classes.

Yeshayahu also explained that one of his goals in writing and publishing the Encyclopedia was to revive the ancient splendor of the Hebrew language and the historical Hebrew names of places in Israel, as well as to correct popular errors and inaccuracies. He concluded with a call for the establishment of a scholarly committee tasked with reviving the historical Hebrew names of “the hills and mountains, the valleys and ravines, rivers and streams,” and developing guidelines for naming all types of geographic formations. Yeshayahu offered to contribute a tenth of the prize money towards the initial expenses in forming this committee.

Sharing the 1948 award with Yeshayahu was Moshe Shamir, author of the bestseller "He Walked in the Fields," the story of the early days of the Palmach. Taking place in 1944, it tells of the fighting with both the Arabs and the British, and the love of two young people, Uri, the Palestine-born Sabra, and Mika, the Holocaust refugee from Poland.

In 1952, Yeshayahu was honored as one of the 12 torchbearers, individuals recognized for their outstanding contributions to society, at the official ceremony marking the closure of Yom Hazikaron (Memorial Day) commemorations and the opening of Independence Day celebrations in Israel. Representing the “Old Yishuv” (the Jewish community in Palestine before the 20th century), he concluded his brief speech with the words "To the glory of the State of Israel!", the phrase still used today by the torchbearers.

Also in 1952, his daughter Chaya passed away, adding to the chagrin caused by Haim’s sudden death at the age of 47 two years earlier. In December 1953, Miriam, his beloved wife and companion for fifty-five years, passed away. [10] He continued to work, preparing the third and fourth volumes of the Encyclopedia for publication, updating the entries with newly gathered information, and adding entries for new settlements. In addition to publishing articles on Jerusalem and Israel and writing his memoirs, he participated in the newly formed government committee—which he proposed—for naming and renaming Israeli settlements, as well as a naming committee for the streets of Jerusalem, among other public services.

Yeshayahu’s letters from this period to his only surviving child, my father, still discuss the scarcity of food. The new state of Israel, with minimal resources and no foreign currency, and the urgent need to absorb close to a million refugees (most of them expelled from Arab countries), imposed rationing and other emergency measures, launching the “austerity period” that lasted ten years. Given his experience with rationing during the siege of Jerusalem, Dov Joseph was appointed Minister of Rationing and Supply in the first Israeli government. Each month, every citizen would receive food coupons for staple foods (later expanded to include furniture and footwear). The diet chosen allowed a meager 1,600 calories per person, with additional coupons (and calories) allotted for children, the elderly, and pregnant women.

My father left Israel in 1950 with my mother and my year-and-a-half-old brother to specialize as an obstetrician-gynecologist, first in Ireland and then, until mid-1953, in the United States. A letter from March 2, 1952, is typical of Yeshayahu’s correspondence in that period: “The state of our diet is deteriorating and the prices go up.” He was promised 100g of meat once every two weeks, and milk is available, but it is mixed with milk powder. Onions could only be obtained at the black market for an exorbitant price.

Not only was food scarce, but something no less critical for Yeshayahu—paper. “Austerity” meant the continuation of the difficulties he experienced in the late 1930s and throughout the 1940s in obtaining paper for the printing of his Encyclopedia. In this 1952 letter, Yeshayahu mentioned asking B’nai Brith in the U.S. to supply the paper required for the publication of the volume of scholarly essays which was dedicated to him on his 75th birthday, i.e., in 1949… [11]

Yeshayahu died in a Jerusalem hospital following a botched operation on June 11, 1955. In what was probably his last letter to my father in Haifa, on May 20, he wrote: “I feel good. The manager of the radio broadcast in French for new immigrants asked me to give a series of lectures on the history of Jerusalem, its neighborhoods and streets, and the meaning of street names. They have translated my written lectures and will broadcast them every Friday at 6:30 p.m. I am waiting for the completion of the printing of the fourth volume [of the Encyclopedia] any day now. The last galley has been in the printer's hands for over two months. The publisher plans to host a party to celebrate the publication of the last volume, possibly at the [Israeli] President’s house.”

The Jerusalem Post reported: “Yeshayahu Press, one of the outstanding veterans of Jerusalem, died yesterday at Ziv Hospital in Jerusalem aged 81 after a short illness.” Professor Benyamin Mazar, President of the Hebrew University, wrote for the Post: “Yeshayahu Press’ outstanding characteristic was perhaps his devotion to his work. His Encyclopedia of Eretz Yisrael represented 40 years of painstaking labor, day and night… He was an honest man and an honest scholar. From his youth, he devoted himself to the study of the country, its historical geography in particular, and made considerable contributions in this field… A true talmid haham,[12] he was ever ready to assist young scholars in their research efforts. Press was a fountain of knowledge on all that pertained to Jerusalem. With his passing, we lose one of the last intellectuals of old Jerusalem.”

I came to Israel in December 1995 to help my father sort through more than one hundred years of family documents and what remained of my grandfather’s extensive library. It’s possible that my mother’s passing a year earlier reminded him of his mortality, and he decided, quite reluctantly, to finally respond to years of pleading by the Zionist Archives. [13]

The first words I heard coming out of the terminal at Ben-Gurion airport were “come on, come on” in Russian. A group of new immigrants and their numerous, massive, striped canvas suitcases were marshaled into a large van, presumably taking them to an absorption center. Or maybe not. No longer were these immigrants, as was customary in previous emigration waves, required to spend their first months in an “Ulpan,” an absorption center where they were immersed in and forced to learn Hebrew. The results of this new, accommodating policy became very evident to me over the rest of my week-long stay in Israel, as Russian was everywhere—on signs and notices, in newsstands, on the streets, and on television.

The headline news, however, was not about immigrants. Every day, Israeli television was showing another evacuation of a major West Bank city, following to the letter Israel’s commitments in the Oslo Accords. As the Israeli military withdrew from each town, Yasir Arafat called to declare, “To Jerusalem, to Jerusalem!” and the mayor of each municipality answered, “To Jerusalem, the capital of the independent Palestinian state.”

The Palestinians were very clear and vocal about their preferred process of state creation. When Arafat announced in Nablus his candidacy for President of the Palestinian Authority, the crowd chanted: “With our souls, with our blood, we will redeem you, Abu-Amar!” Arafat corrected them: “With our souls, with our blood, we will redeem Palestine!” [14] Arafat went on to list all the cities of Gaza and the West Bank, and the timetable for their evacuation, which was “agreed on with the government of Israel,” ending with Jerusalem. Haaretz called this blatant lie about Jerusalem “Arafat’s familiar mentions of the future of Jerusalem” and considered it no more than a “campaign speech.”

In an event in Gaza commemorating its 8th anniversary, with 30,000 Palestinians in attendance, Hamas declared it is not going to participate in the upcoming elections. The official announcement said: “We are going to continue the Jihad until we liberate all of Palestine… the Oslo elections will not give us our rights.”

Israelis had a different idea about Palestine and the process of state creation and development. They have always wanted to improve it for the benefit of all its inhabitants, focusing first on making the desert bloom. Then they invented Startup Nation, deploying the only resource they had in abundance, their brains, assisted by an egalitarian and open culture and the experience of defying all odds for so many years on so many dimensions.

The influx of close to a million new immigrants from the former Soviet Union in the 1990s helped drive this new ambition—applying innovation to all areas of human endeavor, not just agriculture. The resultant increase in the standard of living changed the Israeli landscape, especially the urban landscape.

Many parts of Jerusalem in 1995 were exactly as dilapidated and downtrodden as they had been four decades earlier during the period of austerity, or twenty years earlier when I lived and worked there. Israel, however, was rapidly transitioning from being a “developing country” to its new status of a “developed country.” Here and there, amid the ancient, dirty, decrepit tiny stores in Jerusalem’s center, one could find, in 1995, bright, shiny, American-style temples of consumerism. “The Bell” (on King George Street) was a brand-new, six- or seven-story temple, full of business-like importance, featuring escalators and glass elevators, and a plethora of bright stores. It was an exact replica of a medium-sized shopping mall in any city, USA. Or so I thought, until I reached the basement. It was an enormous bomb shelter with a large, fortified door.

When Iran fired 574 missiles and 1,084 drones at Israel in June 2025, Alvin Rosenfeld found out that “everyone in the miklat [underground bomb shelter] remained calm, civil, even sociable.” Just like other American visitors, such as Chertoff and Borowsky in 1948, Rosenfeld discovered the true spirit of the always-disagreeing, protesting, complaining Israelis:

What an extraordinary country this is! To say the people are resilient is an understatement. They are that and a lot more.

As I learned in the miklat, one needs steady nerves to live here. Most Israelis seem to have them. Those with us in the shelter were a varied bunch—old and young, religious and secular, new arrivals and longtime citizens. But they are bound up with one another in what they know is a common fate. They are doing what they must to live in their own country and defend it against those who would run them out of here. In the face of such threats, they pull together and act as one.[15]

Footnotes

[1] Dov Joseph immigrated to Palestine from Canada in 1921, at the age of 22, and practiced law in Jerusalem. In 1947, he was appointed Head of the Jerusalem Emergency Committee and, from August 1948, served as the military governor of Jerusalem.

[2] 25-year-old Dani Mass commanded 34 other Haganah fighters on a mission to reach by foot and resupply the blockaded Jewish settlements in Gush Etzion, south of Jerusalem. They were spotted before they could reach their destination and killed in a prolonged battle by hundreds of Arab irregulars and local villagers.

[3] After the Ben-Yehuda Street terror attack, Borowsky wrote: “The people who live here have superhuman guts and patience to absorb blow after blow—from the Arabs, from the British, from all sides. I know that on shmirah (guard duty) tonight, I’ll be gripping the sten gun just a little bit more firmly, for it is events like this that ignite the kind of burning anger which can transform even a peace-loving person into a fighter, a soldier.”

Having just completed a first aid course, Zippy (as she signed her letters to her family back in New York) put on her Magen David Adom arm band and pushed her way through the cordons surrounding the stricken area to set up her own first aid station: “I decided not to wait for official assignments, everything is done [here] in such partisan manner anyhow… every extra hand was needed.” In addition to treating the workers digging up in the ruins, “I collected a group of children, some of them in an awful state, who were wandering about waiting to hear a word of their parents.” She also collected and brought to her room a slightly wounded and very disoriented woman who had lost her entire family in the Holocaust, as the building in which this woman lived and worked had been reduced to rubble. “Are there words to describe senseless human tragedy? Will I, can I, ever forget this day? I am becoming like the Jews who live here: every shock and sorrow nurtures them to grim restraint and fierce dedication.”

[4] David Shimoni, Yeshayahu’s brother-in-law, was a prominent Hebrew-language poet in Palestine (and the recipient of the Bialik, Ussishkin, Tchernichovsky, and Israel prizes), known primarily for his Idylls and epic poems. Occasionally, however, he published satirical verses, including in 1937, at the height of the Palestinian Arab revolt, a compilation titled אִישׁ־אִי וְאִישׁ אַי (דּוּשִׂיחִים) (roughly translated: Dialogues between a man of the island and a man of pains or sorrows). In these verses, he expressed the frustration and anger Palestinian Jews felt about the failure of the British to protect them from Arab attacks and their duplicitous language defending their actions. The man of the island, representing the British, presents himself as the guarantor of peace in Palestine. To the questions of the man of sorrows, representing the Palestinian Jews, about various incidents in which Arabs killed Jews, the man of the island blames the victims (“Why did the doctor open the door in the middle of the night? It’s silly to open the door at night”). In another set of verses on the same theme, also published in 1937, the man of the island brags about providing the man of sorrows with the house he was promised (i.e., the “Jewish National Home” of the Balfour Declaration and the language of the British Mandate in Palestine). But the man of sorrows is surprised to be presented with a small cage as his national home. “It is so small, I can’t even lie down in it; with every move, my head would bang against the roof or the walls,” he exclaims, and the man of the island answers: “You should sit quietly, my friend, you must rest. Better be stuck in one place like a nail. No one will hold it against you after all the years you spent wandering.” The final set of “dialogues” was published in 1940, after the British started to enforce their 1,500 per month quota of Jewish immigrants. Now the man of sorrows lamented his brothers and sisters perishing in Europe, “the wailing of children tears my heart asunder.” To which the man of the island responded with “you'd better remember that you have a roommate and that children make noise and your roommate notified me that this gives him a headache. Is he to blame for feeling bad?” [the text in Hebrew https://benyehuda.org/read/49973#ch1126]

[5] A Survey of Palestine: Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the Information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry. (PDF)

[6] Fitzgerald: “It is nearly 1900 years since the destruction of the city by Titus, over seventeen centuries have passed, since the final dispersion after Bar Kochba's rebellion but "If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning" finds as deep a response-to-day in every Jewish heart as it did when it was uttered by the psalmist during the first captivity. To add to that intensity of feeling, the yearning in the 137th psalm has earned a measure of fulfillment. There are in Palestine some half-a-million Zionists. Their communal settlements are dotted from Dan to Beersheba. They are there by virtue of a provision embodied in the Mandate of the League of Nations. In Jewish eyes, this is no colonization as we understand the term, but a return to take up inheritance.” Report and Map

[7] Deuteronomy 32:25:

The sword shall deal death without,

As shall the terror within,

To youth and maiden alike,

The suckling as well as the aged.

[8] Ernest Bevin was Foreign Secretary in the Labour government, 1945–1951. Abdullah I was the Emir of Transjordan from 1921 to 1946, and then King of Transjordan/Jordan until his assassination in 1951 by a Palestinian associated with the Muslim Brotherhood and/or Hajj Amin al-Husayni.

[9] Mordechai Chertoff wrote to a friend on July 15, 1948: “Tonight the Security Council votes on the American truce resolution; planes (presumably Egyptians, not clear yet) dropped a few bombs in Jewish Jerusalem; the shelling from Arab 100-pounders, which was about a city-block away an hour ago, has stopped, and I’m taking advantage of the electricity to write to you. For the first time since the war began, I was frightened tonight.”

[10] David Shimoni wrote in an obituary three years later: “I have known Yeshayahu Press for about thirty-five years, and I haven’t seen almost any changes in him throughout this period. He has suffered from many taxing troubles during these decades, and no doubt his spirit was depressed by the agony; however, his erect body and upright stature never bent… It was so pleasant to meet him on the streets of Jerusalem, walking with sure steps and raised head, even when he reached the age of eighty. Like a crisp and firm pine tree, a live pine tree…. I met him in other places, but no other location fit his noble profile as well as the Jerusalem frame did… Son of Jerusalem he was, Jerusalem-born, and the grace of the place enveloped him.” Years later, whenever a former student of his found out I was Yeahsyahu’s grandson, he or she immediately straightened up, unconsciously mimicking his erect, upright posture.

[11] Titled Yerushalayim: Review for Eretz Israel Research and edited by M. Ish-Shalom, M. Benayahu, and A. Shohet, it was published in 1953—with paper supplied by the Israeli government—by the Rabbi Kook Foundation. It opens with a comprehensive bibliography of Yeshayahu Press’s works.

[12] Talmid Chacham here means a scholar. The phrase is derived from Talmid Chachamim, meaning “student of sages.” In his obituary for Yeshayahu Press, David Shimoni wrote that he was a “talmid chacham in the best meaning of the phrase, that a wise man always learns from others and from everything he encounters. He did not stop studying and adding knowledge almost to his last day.”

[13] The Central Zionist Archives file containing the Yeshayahu Press (Press, Jesajas) documents.

[14] The popular phrase “free Palestine" is derived from the usual translation of “Bil-ruch, bil-dam, nafdika ya Falasteen” as “with our souls and our blood, we will free Palestine.” However, nafdika means "we will sacrifice for you" or "we will redeem you" and is commonly used in phrases like "Bil-ruch, bil-dam, nafdika ya Aqsa" (with our souls, with our blood, we will sacrifice for you, Al-Aqsa).

[15] “Israel Goes to War, and Dancing Breaks Out,” Wall Street Journal, July 11, 2025.

Selected Sources

Yeshayahu Press, One Hundred Years in Jerusalem, Rubin Mass, Jerusalem 1964 (in Hebrew)

Yoram Elmakias, The Map of the Hebrew Association for Jerusalem 1942–1953, Land of Israel Studies, Orot Israel Academic College, Elkana, 2019 (in Hebrew)

Dov Joseph, The Faithful City: The Siege of Jerusalem, 1948, Simon and Schuster, 1960

Zipporah Porath (Borowsky), Letters From Jerusalem, 1947-1948, Porath Publishers, 2015

Daniel Chertoff, Palestine Posts: An Eyewitness Account of the Birth of Israel, based on the letters of Mordecai S. Chertoff, Toby Press, 2019

Jeffrey Herf, Israel’s Moment: International Support for and Opposition to Establishing the Jewish State, 1945–1949, Cambridge University Press, 2022

Thank you for writing and send us this beautiful story of not only your grandfather but of Eretz Israel before it became the State of Israel today. The events described show us that Arab Muslim hostility to the Jews and their state has a long history, as does British perfidy now joined by the western leaders whose chancelleries the British colonized. Simply reading the history of your family, the labor of your grandfather, the steadfastness with which they reclaimed the land and restored Jewish culture and sovereignty therein brought tears to my eyes and balm to my soul. Kol hakavod. May your readers understand why now more than ever only Jewish sovereignty over Gaza, Judea and Samaria will bring peace to our beloved country.